Unfortunately, when it comes to combat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), additional mental illnesses occurring with combat PTSD is almost the rule, rather than the exception. When one diagnosis exists with another, this is known as comorbidity. Studies have found that of veterans with combat PTSD, about half have an additional, current mental illness diagnosis. Comorbidity makes treating combat PTSD more complicated and, of course, tends to increase suffering for the patient. Here is some more information about mental illnesses that commonly occur with combat PTSD.

Effects of Combat PTSD

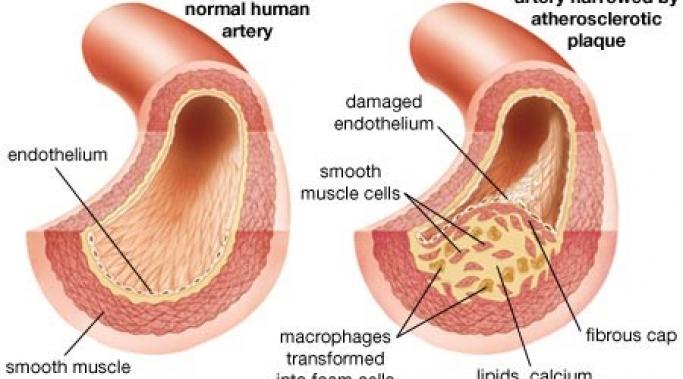

New research indicates that older veterans with combat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are at greater risk for vascular disease. We know that combat PTSD affects the brain and the body in a myriad of ways and now we are coming to understand that one of these ways is vascular.

While it’s something that many people don’t want to talk about, sex matters to people. Sexual function and sexual desire can be important parts of a person’s life, particularly if he or she is in a relationship. And, unfortunately, what we know is that combat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) affects a veteran’s sexual desire and sexual function in negative ways. In fact, some studies have showed such a correlation between sexual dysfunction and PTSD that some have proposed making it an official, diagnostic criteria.

A few weeks ago, I discussed how hyperarousal (or feeling “keyed up”) is a symptom area of combat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A symptom that is part of hyperarousal is an exaggerated startle response. But what is this response and what might this PTSD symptom look like?

A while back I wrote an article on how symptoms of combat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can be seen in the children of veterans. Not surprisingly, PTSD symptoms can also be seen in some spouses of those with combat PTSD, even though the spouse never directly went through the trauma the veteran did. This is often known as secondary traumatic stress or secondary traumatic stress disorder.

Like with all mental illnesses, what happens in the brain to cause combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) cannot fully be explained; nevertheless, there are many things that we do know. We do know what parts of the brain are involved in a stress response and we do know what neurotransmitters are involved and the types of medication that can be used to correct some of those systems.

When one enters the military a thought that may cross the mind of the young soldier, or their loved ones, might be the possibility of dying in combat. This is a reasonable concern for all involved.

But what people rarely are concerned about is the risk of death when one gets out of the military. While it might seem, to civilians, like this would be the least likely time in a person’s life to die by suicide, the numbers tell a completely different story.

Whenever a tragedy occurs, it is natural to look for someone or something to blame, even when the blame isn’t rational; and no one is guiltier of this than the media. This was clearly evident in the way the media treated the tragic Fort Hood shooting last week in which Spc. Ivan Lopez shot and killed three people and wounded 16 others before taking his own life. Instead of just reporting these facts, many in the media tried to tie these actions to combat-related posttraumatic-stress disorder (PTSD). And while Spc. Lopez was being evaluated for PTSD, there is no way of knowing whether his actions were in any way related to the disorder and insinuating such does a great disservice to veterans and those serving in the military. In fact, all the media has done is further stigmatize PTSD.

In the last two articles I commented on how combat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can be transmitted between parent veterans and their children and what combat-related PTSD might look like in the children of veterans. Today, I talk about what a parent with combat PTSD can do to fight its effects in his or her children.

Last week I discussed the fact that combat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can be transmitted to children from their parents in cases where a parent suffers from combat PTSD. This intergenerational transmission of trauma, or secondary PTSD, can drastically impact a child’s behaviors. Symptoms of combat PTSD in children can range from hyperactivity to extreme withdrawal.