Not everyone who self-harms does so out of anger. Even when self-injury is fueled by rage, participating in self-inflicted violence doesn't automatically make you a violent or aggressive person.

Stigma of Self-Harm

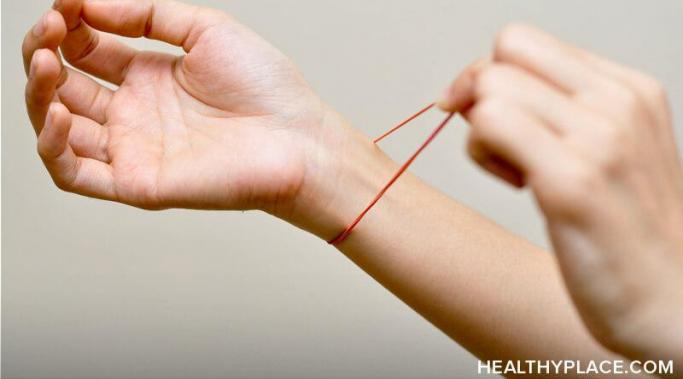

The secret shame of self-harm is a heavy burden—one that, especially when borne alone, can slow us down and hinder the healing process. Self-harm recovery begins with learning to let the shame of self-harm go.

It's one thing to tell someone you've hurt yourself accidentally. But what do you say when you hurt yourself on purpose? What's the best way to tell someone you self-harm—and who should you tell first?

While self-injury can sometimes be a precursor to suicide, self-harm and suicide are not inextricably linked. Blindly assuming one always leads to the other can potentially hinder, rather than support, the healing process. (Note: This post contains a trigger warning.)

Misinformation doesn't just trick other people into believing stigmas surrounding self-harm—those of us struggling with it may fall prey to false self-injury beliefs, too.

Feeling guilty about self-harm scars isn't uncommon—but it isn't necessary, either. Accepting your scars takes time, but it's an important part of healing.

Is self-harm a sin? Whatever you believe in life, if you've asked yourself this question (or one like it) before, know that you're not alone.

The paradox of self-harm can be difficult to understand, even for those of us living inside it. We hurt ourselves to feel better—and no, on the surface, that doesn't make sense. But in the moment, sometimes it feels like the only option we've got.

Not every case of self-injury is obvious. Whether you're talking clinically or colloquially, it can be hard sometimes to clearly define what counts as self-harm and what does not.

Individually, hating yourself and hurting yourself are difficult things to cope with. Simultaneously, though, self-harm and self-hate create a vicious cycle that can be challenging to break—but doing so is vital for healing and growth.