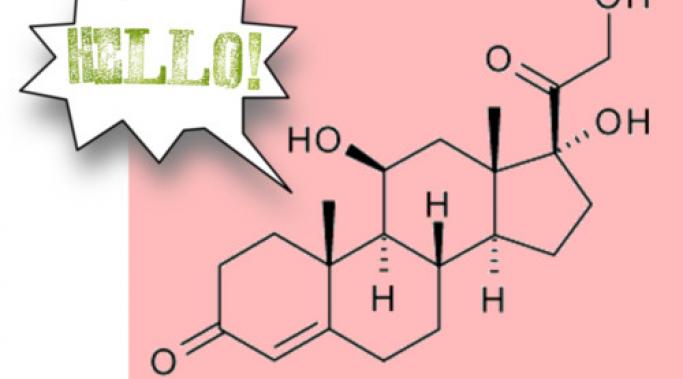

About a year ago it occurred to me that managing cortisol might directly impact symptoms of Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Because cortisol is an adrenal hormone secreted during periods of high stress, it seemed logical that people with trauma disorders would have higher-than-average cortisol levels. The symptoms of cortisol imbalance supported that idea, and since taking the steps to stabilize those theoretically high cortisol levels could do me nothing but good either way, I launched an experiment. I quit smoking, swore off dieting, and tried to get better sleep. Did it help?

Dissociative Living

Trauma disorders like Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) come with a host of chronic problems. Cortisol imbalance - either too much or too little of this adrenal hormone sometimes referred to as the "ultimate stress hormone" - might be one of them. But why bother investigating something that might be a problem, when there are so many things that are? I'm a curious person. And I've got a hunch that managing cortisol might directly impact symptoms of Dissociative Identity Disorder and PTSD, which in turn helps balance cortisol levels, which alleviates symptoms, and around and around we go.

I have Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), trauma disorders that are both: 1) responses to overwhelming stress, and 2) sources of continuing high stress. Cortisol is an adrenal hormone our bodies create to help us cope with extreme stress, physical and emotional. I began researching the signs and symptoms of cortisol imbalance when it occurred to me that living with DID and PTSD (or any chronically, very-high-stress condition or situation) would logically mean living with elevated levels of cortisol. And whaddyaknow? The top five symptoms are also the top five most frustrating, debilitating, and chronic issues in my life.

Last fall, I started reading more about cortisol, an adrenal hormone perhaps best known for its role in the fight or flight reaction. I’d heard a lot of chatter about how we’re all drenched in the stuff on account of modern life is like fighting hungry lions only without all the hungry lions. And it occurred to me that if busy work schedules and not enough down-time could produce enough excess cortisol to get medical doctors pushing things like meditation, living with trauma disorders like Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) must be as dangerous as battling a pride of hungry lions on the edge of an active volcano during a hurricane.

When I published my last post almost a year ago, I was sure that it marked the end of Dissociative Living. I wasn’t happy about that. I was frustrated and angry with myself for what I saw as an inability to manage stress effectively. And I was sad that I had to give up writing about Dissociative Identity Disorder because of that inability. Since that post last September, I’ve learned some things, including: 1) there is a profound difference, practically speaking, between stress and chronic stress, and 2) you cannot manage chronic stress – you either survive it, or you escape it.

I'm weary. I’ve been living on the wrong side of my stress threshold for a while now. Part of the problem is that my stress threshold is maddeningly low. But part of the problem is that major things keep happening in my personal life lately; things that create enormous stress even for the most mentally healthy among us. As a result, my Dissociative Identity Disorder symptoms have amplified steadily over the last eighteen months. In the words of my fellow blogger Natasha Tracy, “When life gets nasty disease gets nasty too.” She’s right, of course. But I kept thinking, ‘hey, life is really turbulent sometimes and you just have to rise to the occasion.’ I failed to recognize, though, that doing so usually involves letting go of other, less urgent occasions.

Over the years I've heard many people advise dropping the word 'disorder' from dissociative identity disorder, citing

A) dissociation as a normal response to trauma, and

B) honoring subjective experiences as the primary reasons that it’s not helpful.

But the degree to which something is normal really has nothing to do with whether or not it’s a disorder. Disorders are referred to as disorders not because they're abnormal, but because they actively, regularly, and severely disrupt people's lives to such an extent that their ability to function is notably, even dangerously, compromised. And labeling a particular set of psychiatric symptoms with a particular psychiatric diagnosis is no more a call to ignore individual experience than it is to use labels like diabetes, hyperthyroidism, or influenza.

After a recent experience with state-dependent memory recall got me questioning the heavy focus on internal communication in Dissociative Identity Disorder treatment, I decided to ask readers of my personal blog how they learn about their systems. 63% of responders cited feedback from external others along with internal communication as the primary ways they gain insight into their DID systems. Only 9% cited internal communication alone. [See poll.] And yet in the six years since my diagnosis, I’ve never heard anyone who treats or has DID recommend engaging in the outside world as a path to self-discovery. In fact, I’ve heard the opposite: no one will understand Dissociative Identity Disorder but us; talk to yourself and to us, and no one else.

Soon after I began researching anything and everything related to Dissociative Identity Disorder, I came across the idea of state-dependent learning. And though the concept – that things learned or experienced under certain conditions, internal and/or external, are easiest to recall under those same conditions – made sense to me, it didn’t make much of an impression. But recently I had a profound personal experience that illustrated clearly to me both the power of state-dependent learning and the revelation of state-dependent memory recall.

The past few months of my life have brought with them the suicide of a family member, the substance abuse problems and sudden onset mental illness of another, some unexpected financial difficulties, and not nearly enough time and space for me to cope with it all effectively. I’ve taken the put-your-head-down-and-keep-moving approach in part because I know I’ll leave other people in the lurch if I stop to recuperate. When a tornado hits is not the time to announce that gosh, you’d love to help out but you really need some Me Time. Instead, I’ve relied on my long-held belief that Dissociative Identity Disorder is both a blessing and a curse when life gets messy. But I’ve changed my mind. All DID does is make nasty situations nastier.